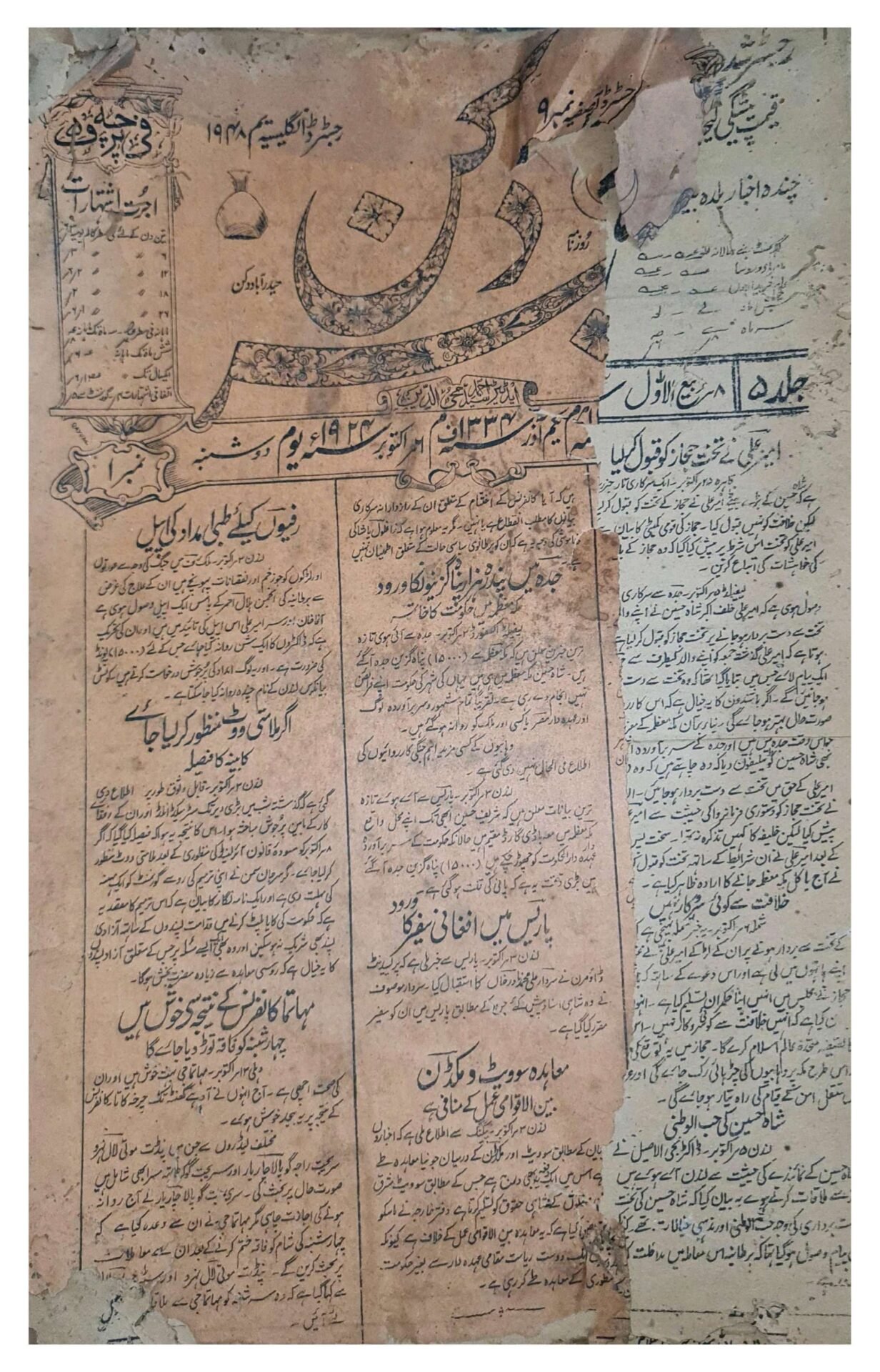

Rahnuma-E-Deccan Daily |Special Report

(RAHNUMA) The abolition of the Ottoman Caliphate in 1924 created not merely an institutional rupture, but a profound theological and political crisis across the Muslim world. While the Turkish Republic formally ended the Caliphate as a state institution, the question of its continuity—symbolic, custodial, and moral—did not disappear. Instead, it migrated into quieter channels shaped by colonial constraints, private diplomacy, religious consensus, and the realities of power in an age of empire. A growing body of archival evidence, contemporary journalism, religious documentation, and later testimony now warrants a serious re-examination of Hyderabad’s role in this transitional moment.

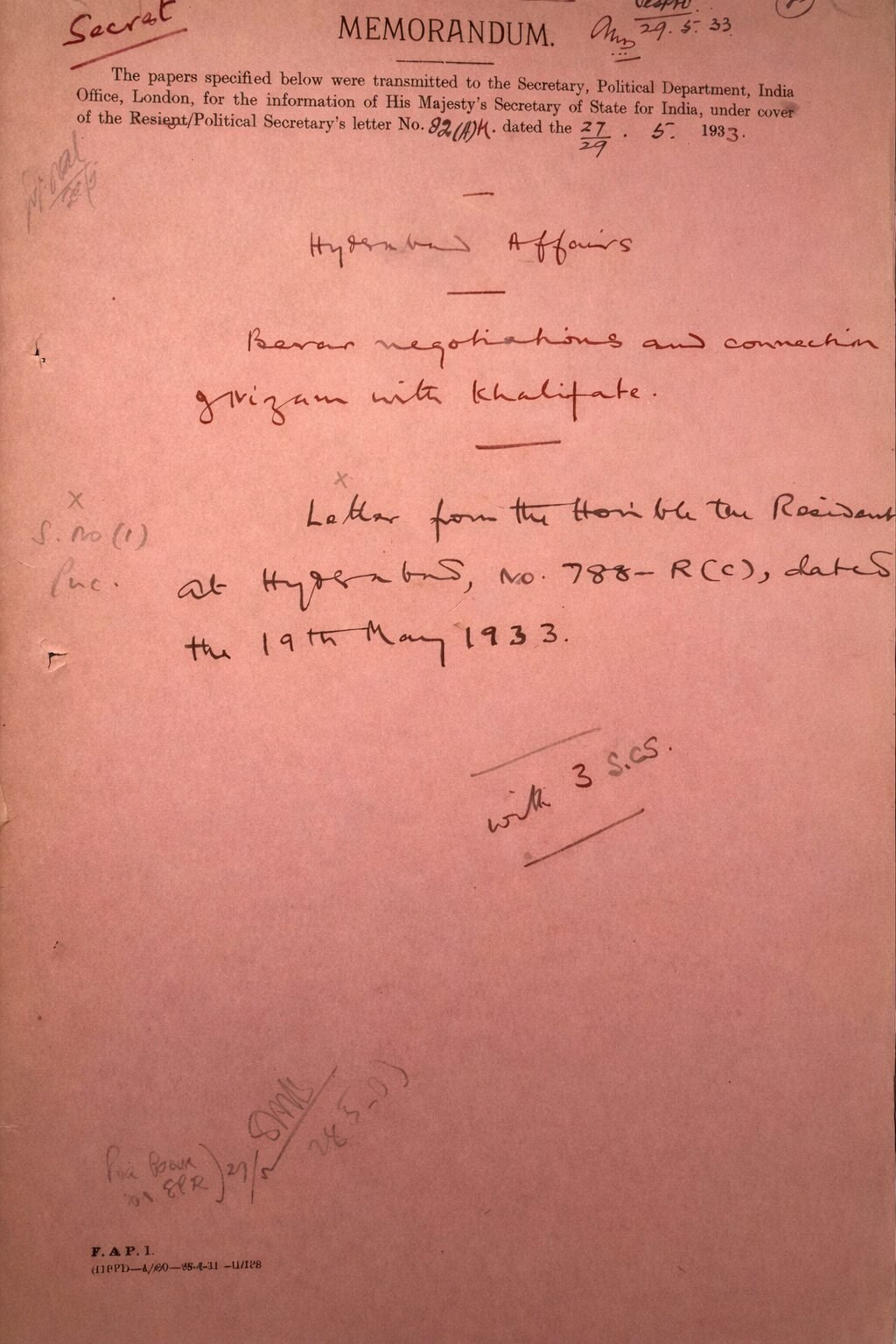

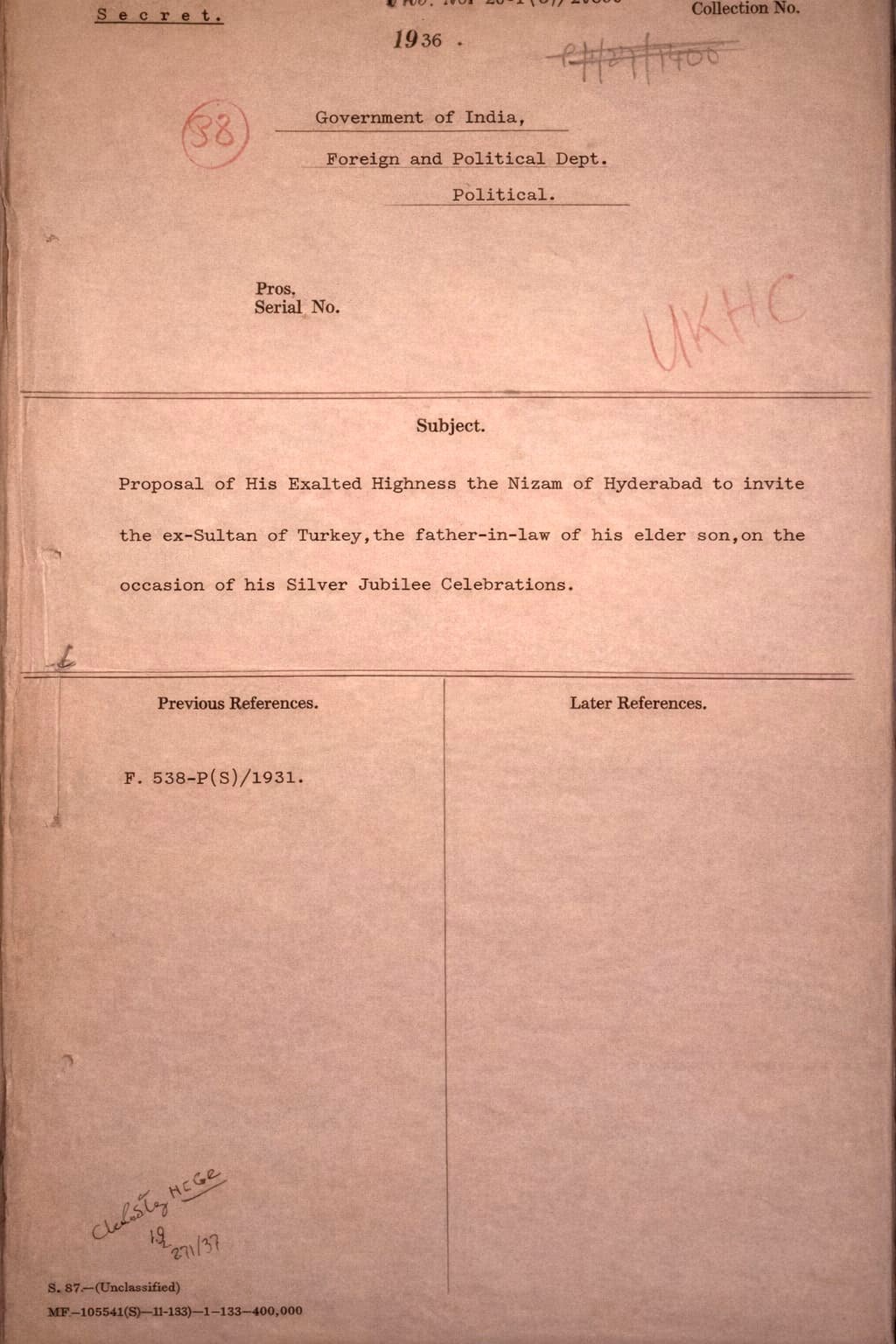

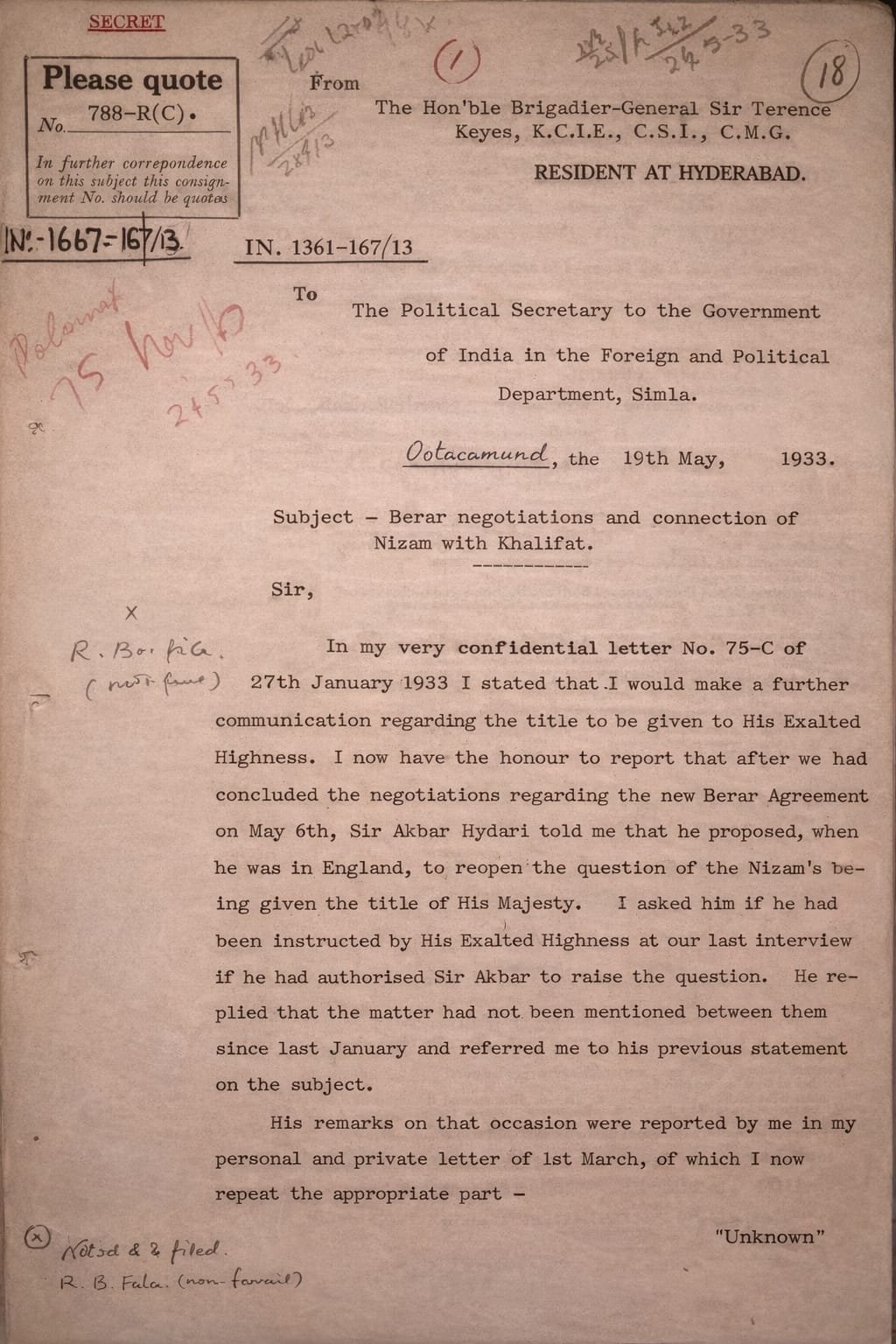

Confidential correspondence between the British Government of India and the Resident at Hyderabad from 1931 to 1936 demonstrates sustained official concern over the Nizam of Hyderabad’s connection with the Khilafat question. These documents, marked Secret, refer explicitly to “Berar negotiations and connection of Nizam with Khilafat,” discussions surrounding titles, and proposals involving the ex-Sultan of Turkey during the Nizam’s Silver Jubilee. The British fixation on titles—particularly the question of “His Majesty”—is notable. Under the Raj, any overt assertion of supranational Islamic authority by a princely ruler would have been politically intolerable. The persistence of secrecy therefore does not weaken the claim; it explains the form it took.

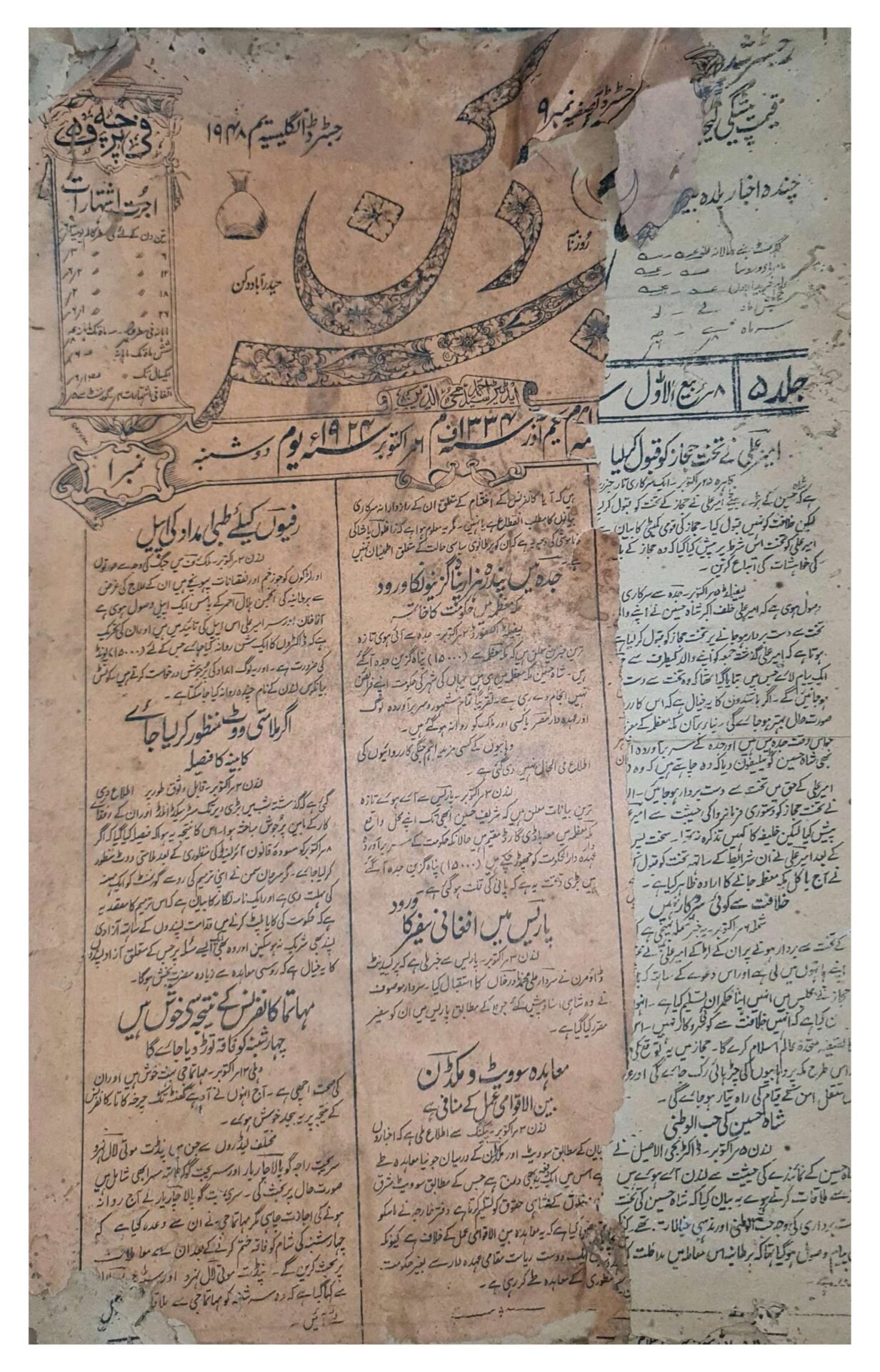

Crucially, Rahbar-E-Deccan recorded that Sharif Ali, successor to Sharif Husayn, explicitly renounced any claim to the Caliphate, declaring that he sought only the welfare of the Arab people. This left a vacuum that was widely acknowledged but nowhere formally filled. It is within this vacuum that Hyderabad’s role becomes intelligible.

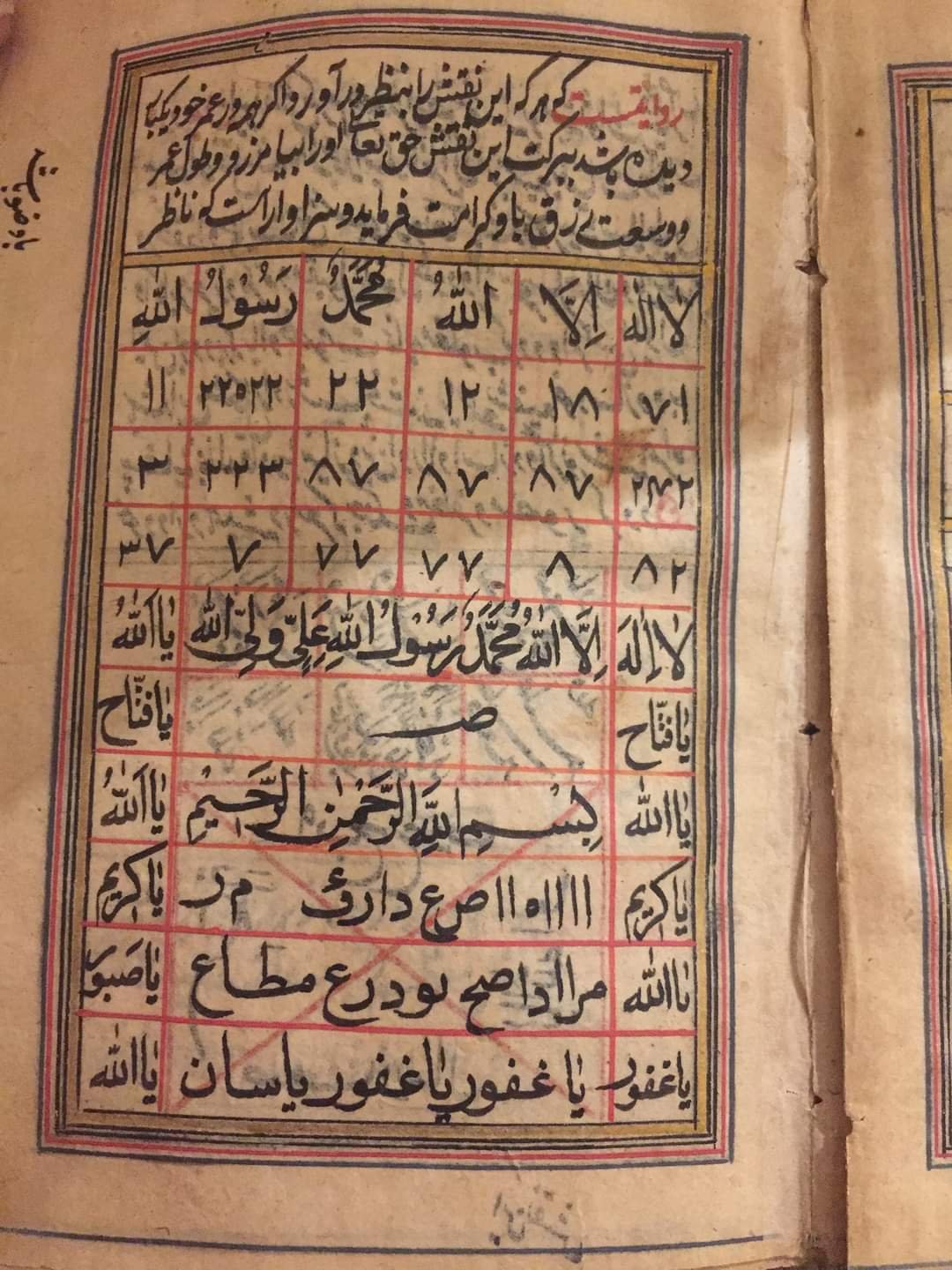

The intellectual and religious framework for such a role had already been articulated in India. At the fourth session of Jamiat-ul-Ulama, held in Gaya in December 1923, leading scholars unanimously affirmed that politics and religion were inseparable in Islam. Maulvi Abdul Rauf argued that Islam had historically known no form of governance other than the sultanate, and that the Caliph, as supreme leader, must possess both spiritual and temporal authority, receiving allegiance from all Muslim polities functioning as delegated sultanates. He went so far as to demand that the Turkish Caliph send a nominee to India to guide Muslims and settle disputes. The speech of Maulana Habibul Rahman of Deoband, read at the same session, reinforced this view, stressing that there could be no Caliph without both spiritual and temporal power, and that his title must remain “His Majesty.”

This insistence on title is critical. It clarifies why British intelligence cables repeatedly fixated on the Nizam’s pursuit of recognition as “His Majesty,” and why the matter resurfaced persistently before the 1936 Jubilee. It also explains the extraordinary appearance of that title in 1947.

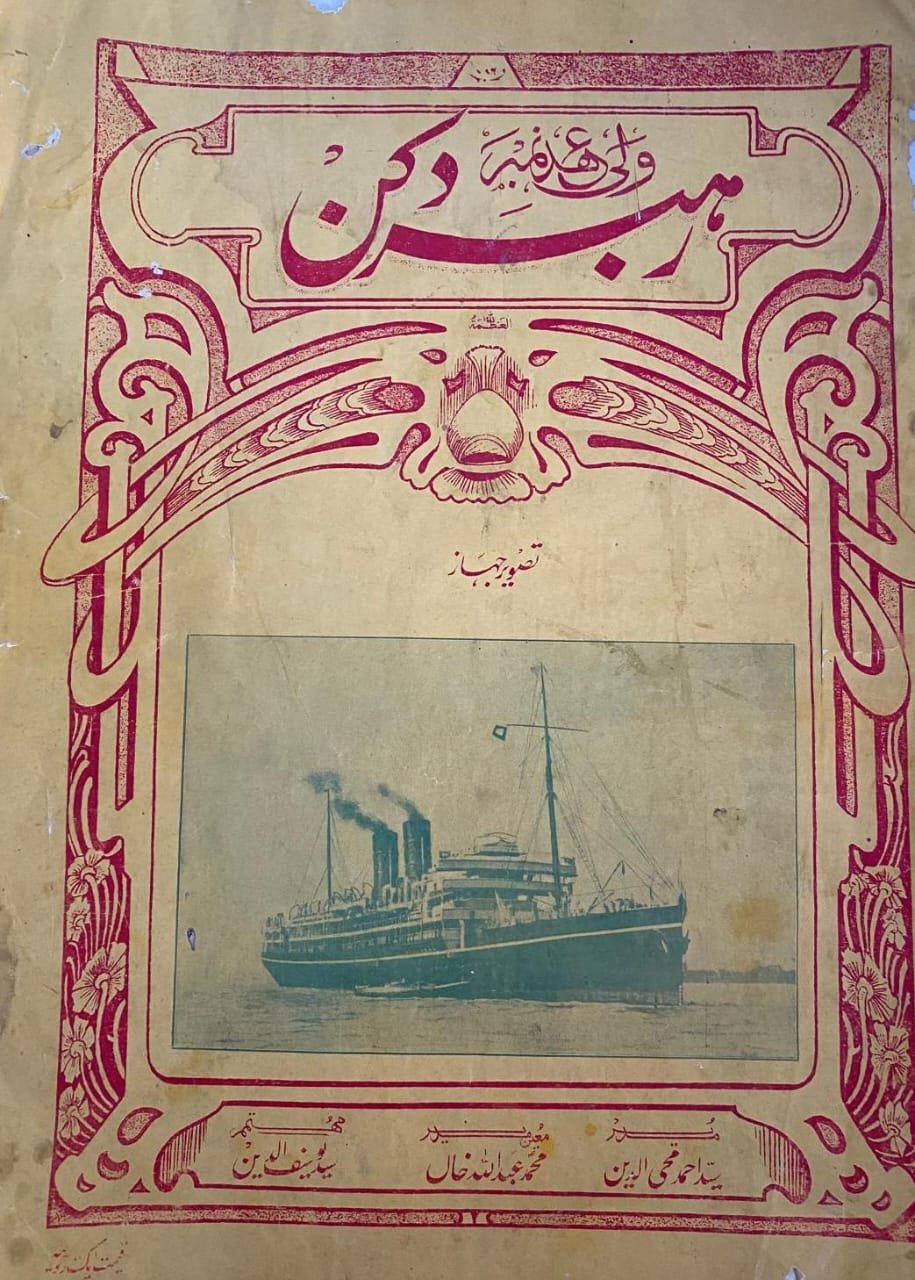

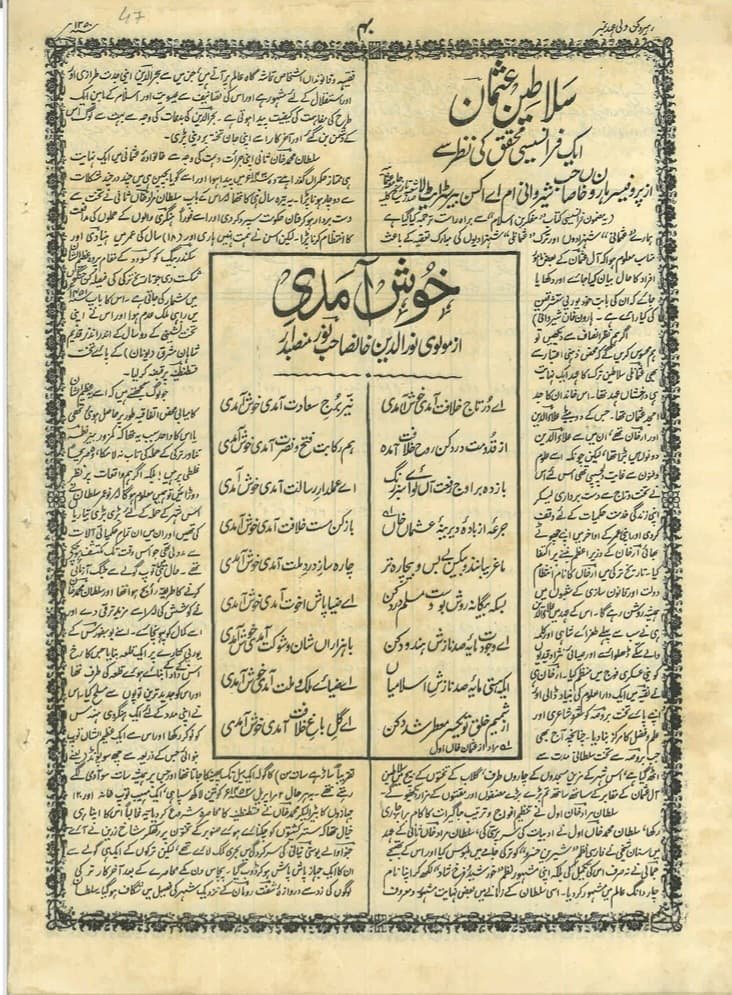

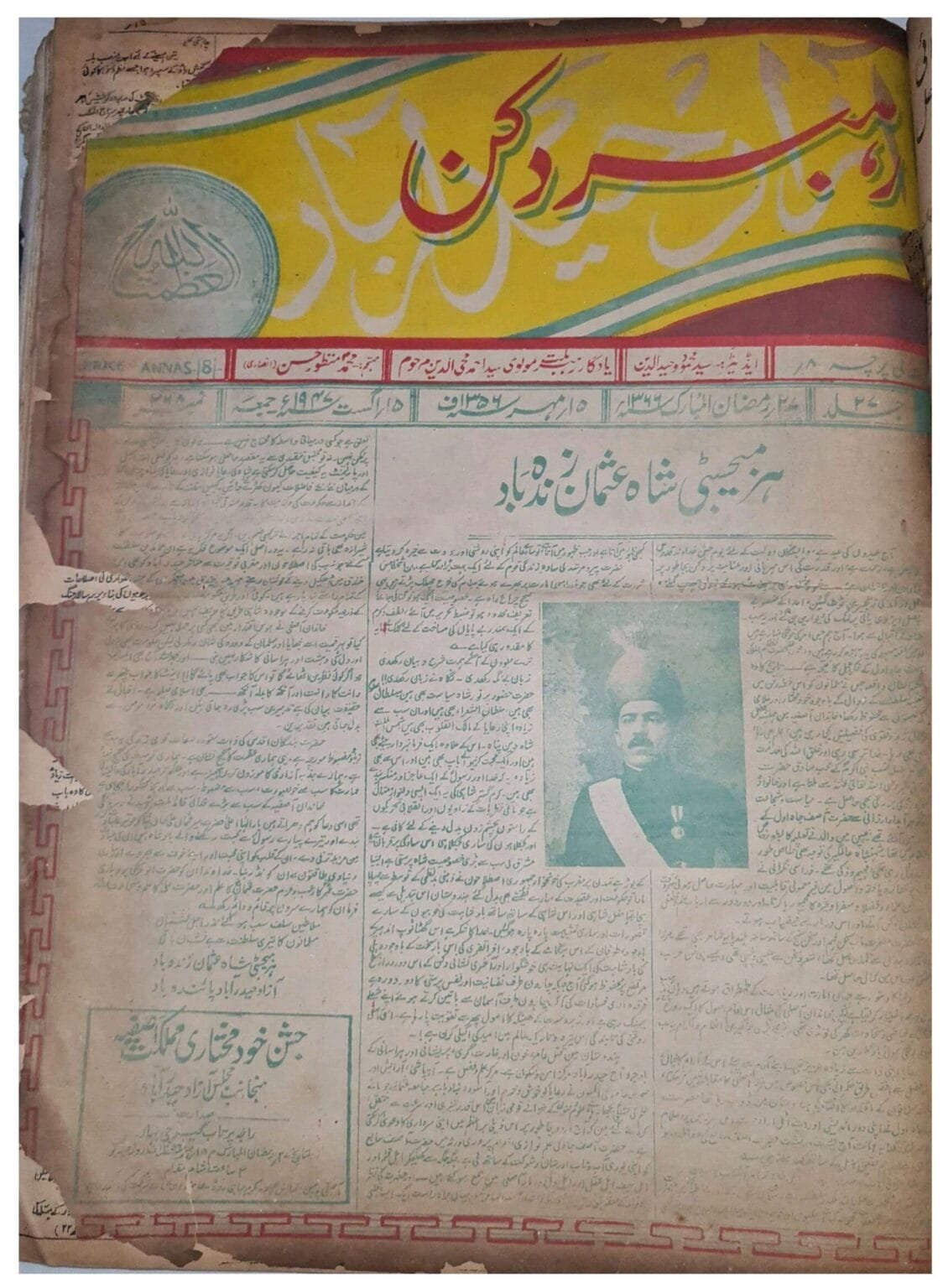

In the 1931 Wali Ahad (Crown Prince) Special Edition of Rahbar-E-Deccan, published under the Nizam’s patronage, page forty contains a poem explicitly welcoming the arrival of the Caliphal Crown (Taj-e-Khilafat) to Deccan. The poem speaks of the reopening of the gates of the Caliphate, the return of illumination to governance, and the revival of a legacy linked to Ottoman Usman Khan I. This was not symbolic nostalgia; it was a contemporary literary announcement, published while Caliph Abdul Mejid II was alive and immediately following the Ottoman–Asaf Jahi matrimonial alliance.

Translation by The Rahnuma-E-Deccan

Welcome! From the pulpit of Maulvi Nooruddin Khan, Mansabdar

You have come to the crown of the caliphate, a great blessing.

You have arrived at the pinnacle of fortune and prosperity, welcome!

Victory and success have accompanied you, welcome!

As the standard-bearer of prophethood, you have arrived, welcome!

The gates of the caliphate have opened again, welcome!

You have come as the solution to governance, welcome!

O light of brotherhood, you have come, welcome!

With grandeur and splendor, you have awakened the dormant world,

You have illuminated the kingdom and nation, welcome!

For the garden of aspirations, you have come as a flourishing flower, welcome!

With your arrival in Deccan, the spirit of illumination has returned,

A legacy has revived, pouring blessings upon it,

A grand sip from the timeless chalice of Usman Khan.*

The poor are now comforted,

The destitute and helpless find refuge,

Even strangers are guided to a noble path.

In this realm, a voice has risen,

The pride of Hindustan,

The glory of Islam.

Indeed, you are the manifestation of a divine blessing in Deccan.

*The fulfillment of aspirations linked to Usman Khan the First.

_____________________

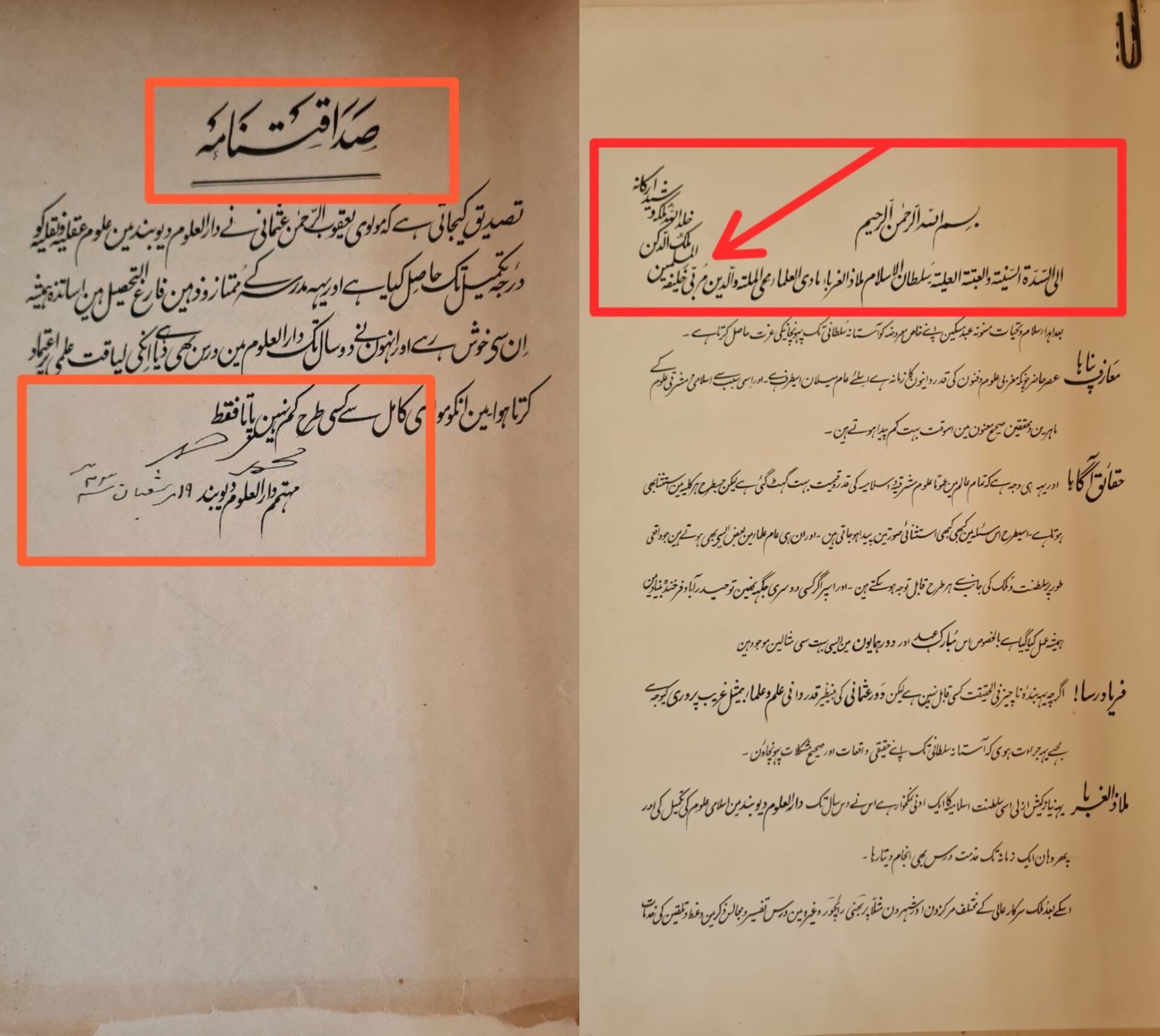

Source: Rahbar-e-Deccan 1931. Wali Ahad Number. Crown Prince Special Edition. Syed Ahmed Mohiuddin, Syed Yusufuddin. 68 pages. Pg. 40. Rahbar-e-Deccan Press, Afzal Ganj, Hyderabad.

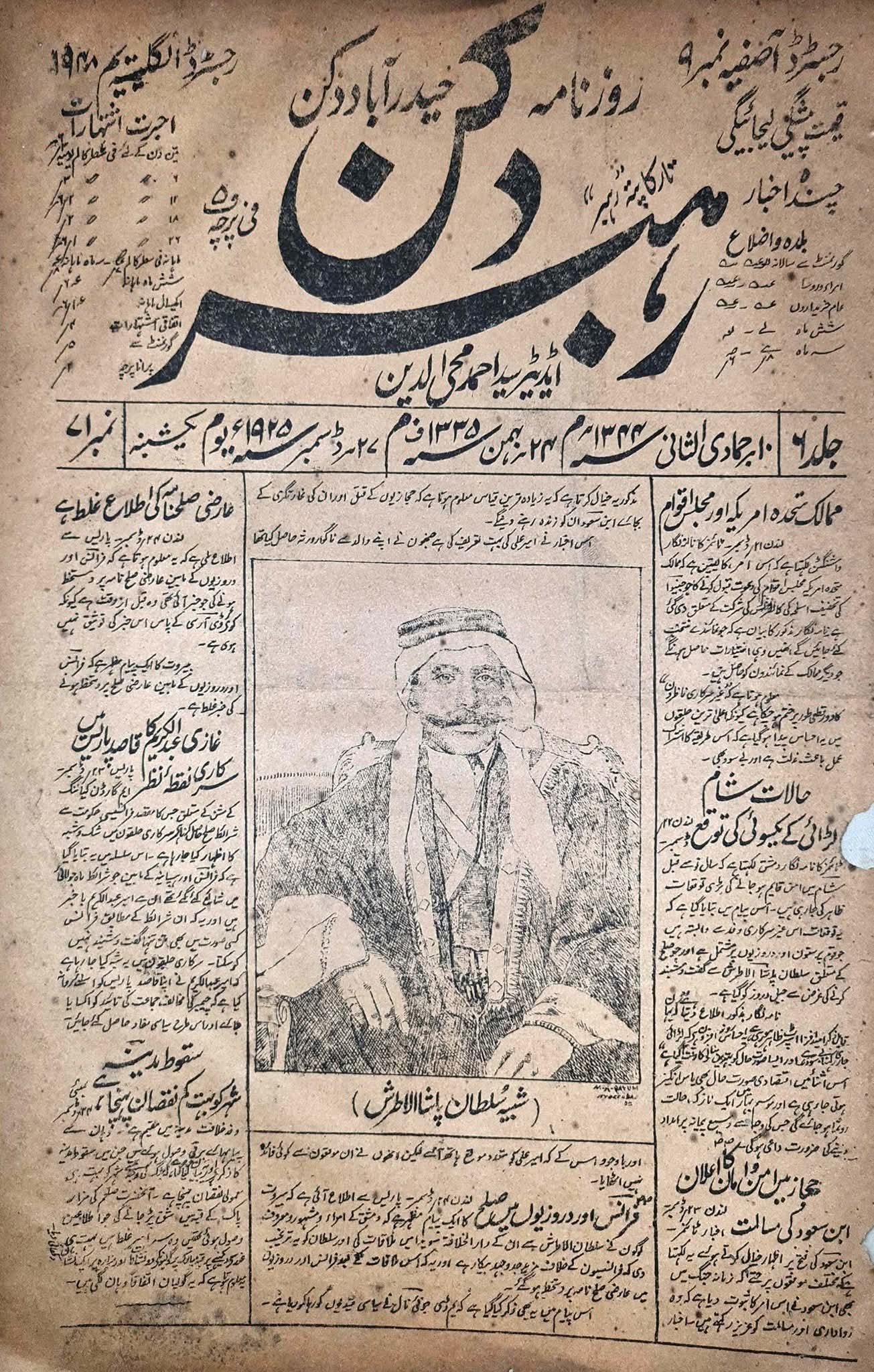

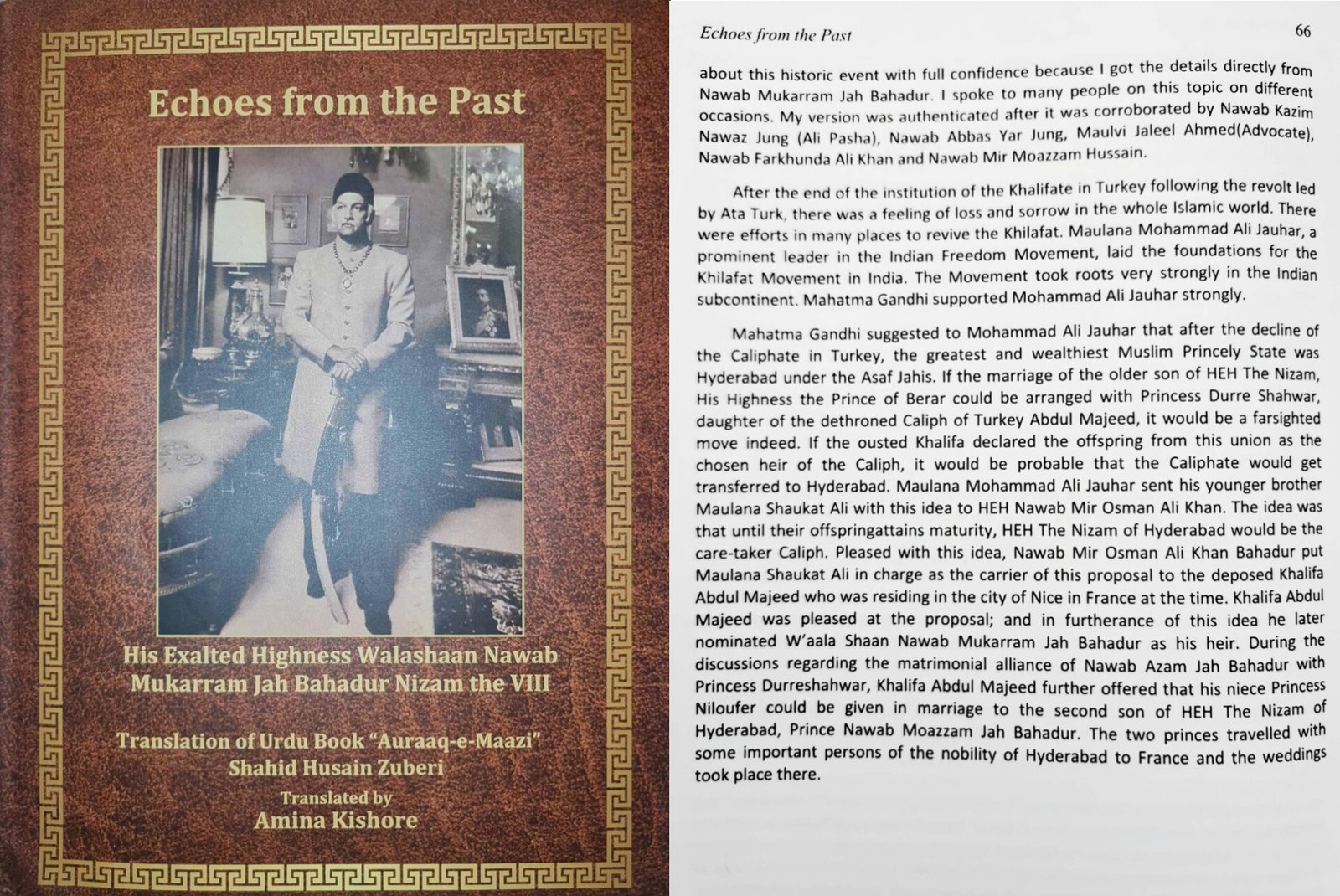

International media took note. TIME Magazine in November 1931 observed that Hyderabad’s ruler had sought Caliphal recognition and that the engagement between the Caliph’s daughter and the Nizam’s heir was viewed by many Muslims as a promising fusion of temporal and spiritual authority. Later assessments echoed this. The Deccan Chronicle (2006) noted that the alliance was believed to offer a Muslim authority acceptable to world powers after the Ottomans, while The New York Times (2023) reported that Caliph Abdulmejid II, in his will, nominated his grandson Mukarram Jah as inheritor of his Caliphal claim, though that claim was never publicly asserted.

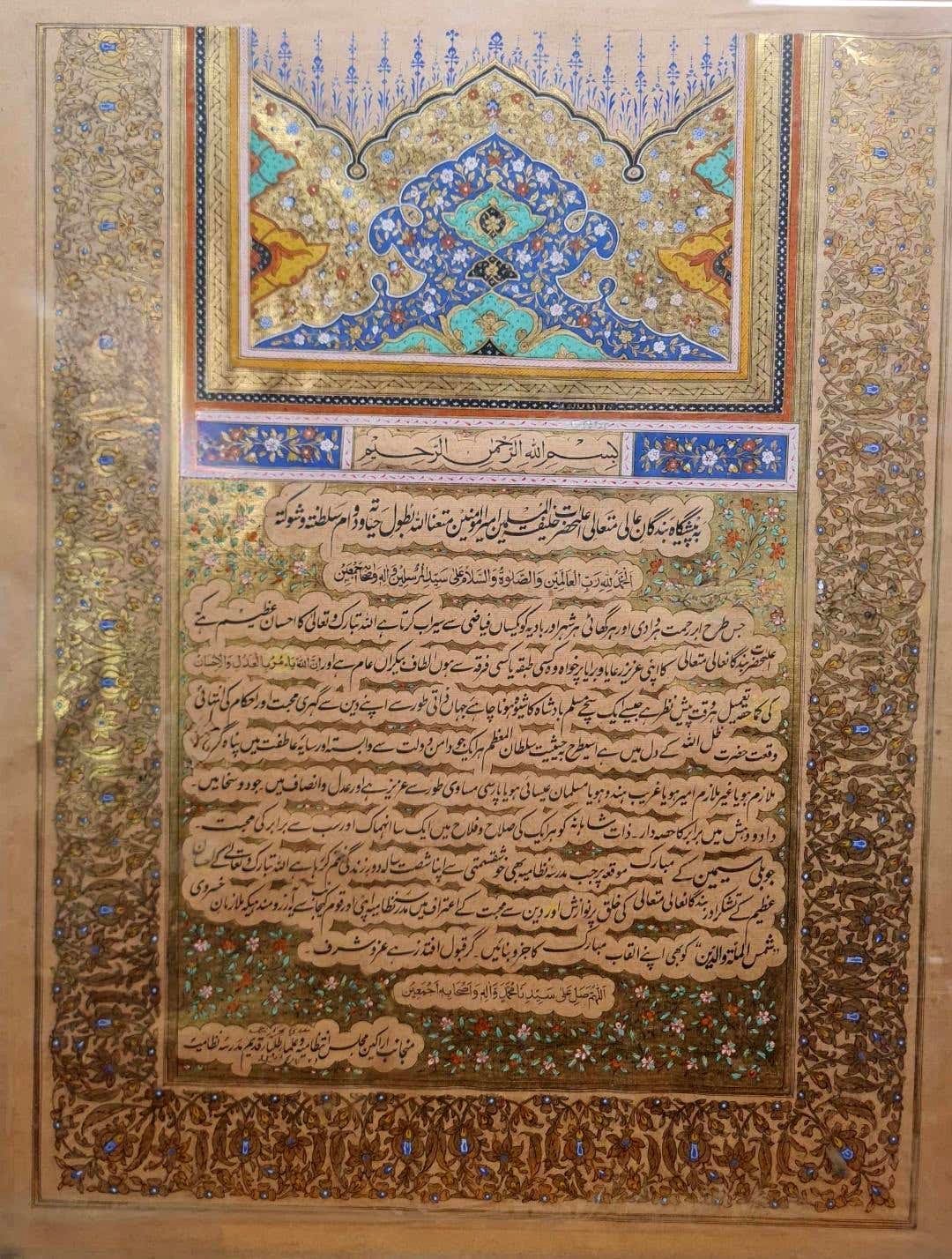

Translation by Rahnuma-E-Deccan

In the Name of God Almighty, Most Compassionate, Most Merciful

To the August Presence of His Exalted Highness, the Most Noble and Most Sublime, the Caliph of the Muslims, the Commander of the Faithful—may God grant him long life and the (continuance) of his sovereignty and majesty.

Praise be to God, Lord of the Worlds, and blessings and peace be upon the Chief of the Messengers, and upon his family and all his Companions.

Just as the cloud of mercy pours forth its beneficence equally upon every valley and ravine, every city and desert, so too is it among the great favors of God Most High that the boundless grace of His Exalted Highness, the Most Noble and Most Sublime, is extended without distinction to his subjects, regardless of whatever class or community they may belong to. The realization, in its fullest sense, of the divine command—“Indeed, God enjoins justice and beneficence”—is ever before him.

As befits a true Muslim sovereign, while there is in the heart of His Highness, the Shadow of God, a deep personal love for his faith and the utmost reverence for its commandments, so also, in his capacity as ruler, everyone who is attached to the hem of the state and who takes refuge beneath the shade of his compassion—whether in service or not, whether rich or poor, whether Hindu or Muslim, Christian or Parsi—is equally dear to him. In justice and equity, in generosity and munificence, all share alike; in concern for the welfare and betterment of each and every one there is the same devotion, and toward all the same measure of affection.

On this auspicious occasion of the Silver Jubilee, when the Nizamia Seminary has also, by good fortune, completed its sixtieth year of life, in gratitude for the immense favor of God Most High, and in acknowledgment of the benevolence of His Exalted Highness toward creation and of his love for the faith, the Nizamia Seminary, on its own behalf, humbly expresses the desire that the august title “Shams al-Millat wa’l-Dīn” (the Blazing Sun of the Community and the Faith) may also be included among his blessed honorifics—so that thereby honor and distinction may be further exalted.

O God, send blessings upon our master Muhammad, and upon his family and his Companions, all of them.

On behalf of the Members of the Administrative Council, the Scholars, and the Students and Alumni of the ancient Nizamia Seminary

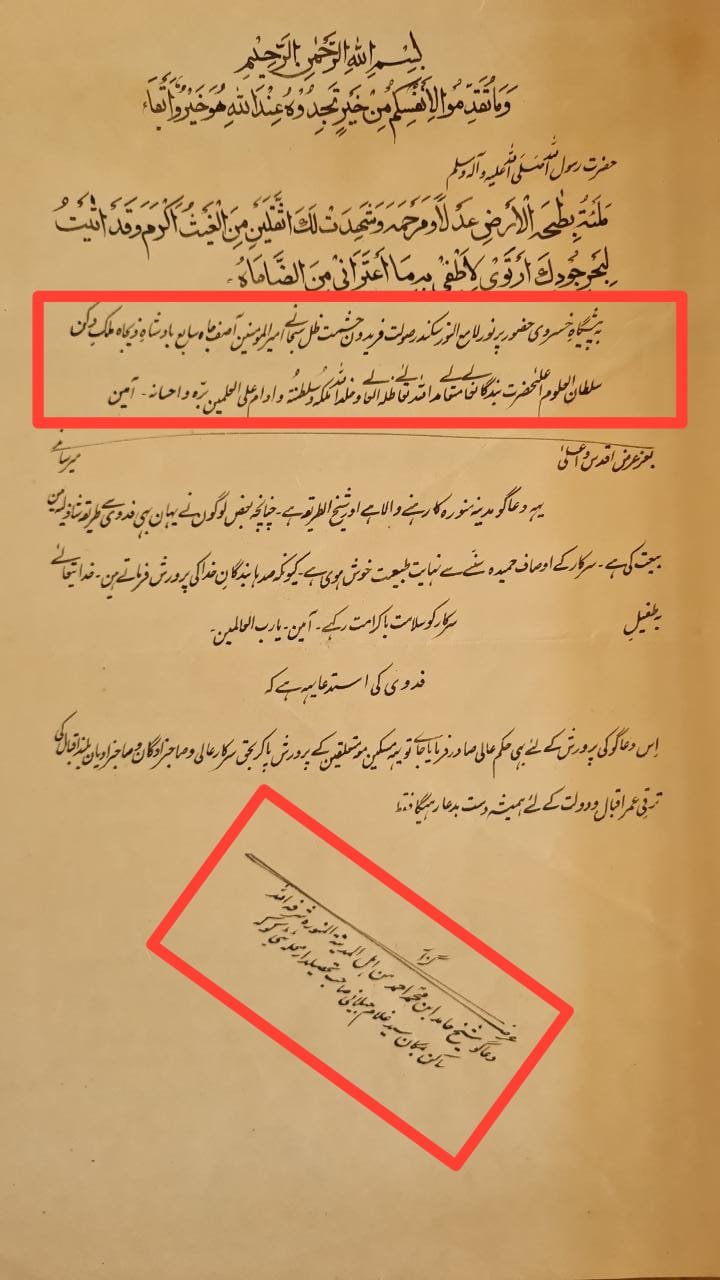

Support was not confined to India. Letters preserved in the Rahbar-E-Deccan archives, addressed to the VII Nizam from Mecca and Medina, refer to him using titles reserved exclusively for the Caliph, including Amir-ul-Mu’minin, and Zill-e-Subhani (Shadow of God). One such letter, seeking employment and accompanied by an attestation from Hafiz Muhammad Ahmed, son of Qasim Nanawtawi and Dean of Dar-ul-Uloom Deoband, implicitly recognizes the validity of these titles and includes Sultan-ul-Islam, and Caliph of Muslims as amongst those accepted for the VII Nizam. Under the British Raj, the remainder of such correspondence was necessarily circumspect, but the language employed is itself revealing.

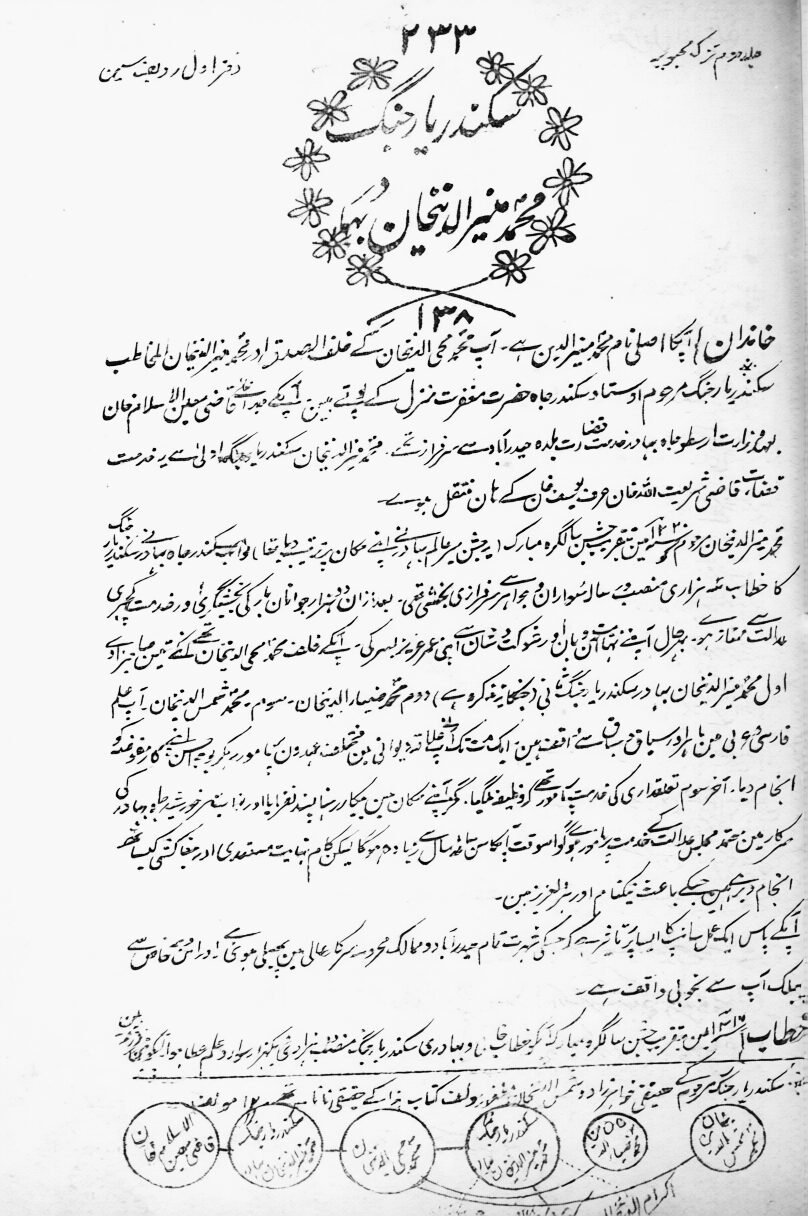

A final dimension emerged publicly only after the death of Prince Mukarram Jah Bahadur. In 2023, during the exhibition The Caliph’s Wonderful World at the Salar Jung Museum—curated in collaboration with Princess Jamila Boularas and Princess Zairin Mukarram Jah—a document was displayed stating that sometime prior to 1967 the VII Nizam entrusted custodianship of the Caliphal Crown to his Military Secretary, a descendant of Secunder Yar Jang I. This lineage, traced in Tuzuk-e-Mahbubiya (p. 298), was historically associated with the religious authority of Chief Justice of Shariah and the title Mu‘in-ul-Islam (Support of Islam). Custodianship was thus placed not arbitrarily but within a family long entrusted with Islamic legal and institutional guardianship in Hyderabad.

This may explain a long-noted historical silence. Despite being nominated by the Caliph and identified internationally as heir, Mukarram Jah never publicly claimed the Caliphal Crown. If custodianship had already been formally entrusted elsewhere, his restraint appears not as abdication but as adherence to an established arrangement. This interpretation is reinforced by his engagement with the Rahnuma-E-Deccan Family, including multiple visits to their residence—then leased by the Government of India for Hyderabad’s first passport office—where he received his Indian passport.

In a rare tricolor Independence Special Edition of Rahbar-E-Deccan dated 15 August 1947, the Nizam appears under a title never used for him before or after: “Long Live His Majesty Shah Osman Khan Bahadur.”

In a Muslim world where no other ruler carried that title, its appearance cannot be accidental. It reflects motive, continuity, and context: a Caliphal claim consciously asserted at the moment of independence, after decades of preparation, restraint, and discretion.

Taken individually, none of these sources constitutes a universally proclaimed restoration of the Caliphate. Taken together, they form a coherent and internally consistent evidentiary continuum. British intelligence records acknowledge the issue; Rahbar-E-Deccan documents its evolution from the fall of Hejaz onward; Deoband and Jamia Nizamia articulate the theological framework; Mecca and Medina provide moral recognition; international media records the implications; and later custodial documents explain the silence.

According to a private letter alleged to have been penned by the VII Nizam Mir Osman Ali Khan to his Military Secretary Lt. Colonel Syed Mohammed Amiruddin Khan some time before the Nizam’s death in 1967, and displayed by Princess Zairin Mukarram Jah in 2023 at the Salar Jung Museum in Hyderabad, the lineage of the Military Secretary’s ancestor Secunder Yar Jung III is traced back to Fatima al-Zahra, daughter of the Prophet Muhammad— like the founder of the Naqshbandi Sufi Order—through the eleventh Shia Imam Hasan al-Askari, father of the Hidden Imam Muhammad al-Mahdi. Thus—after nearly fourteen centuries of separation from the line of the Prophet’s legal heirs—the Caliphal Crown, through its Custodianship, appears to have found its way home, even if just in a ceremonial capacity, and without any claim to religious or political authority, in a manner not unlike the historical plight of the Immaculate Imams of the Children of Fatima, Secunder Yar Jang III’s paternal ancestors.