Why Some Hold On Too Tight, and Others Pull Away

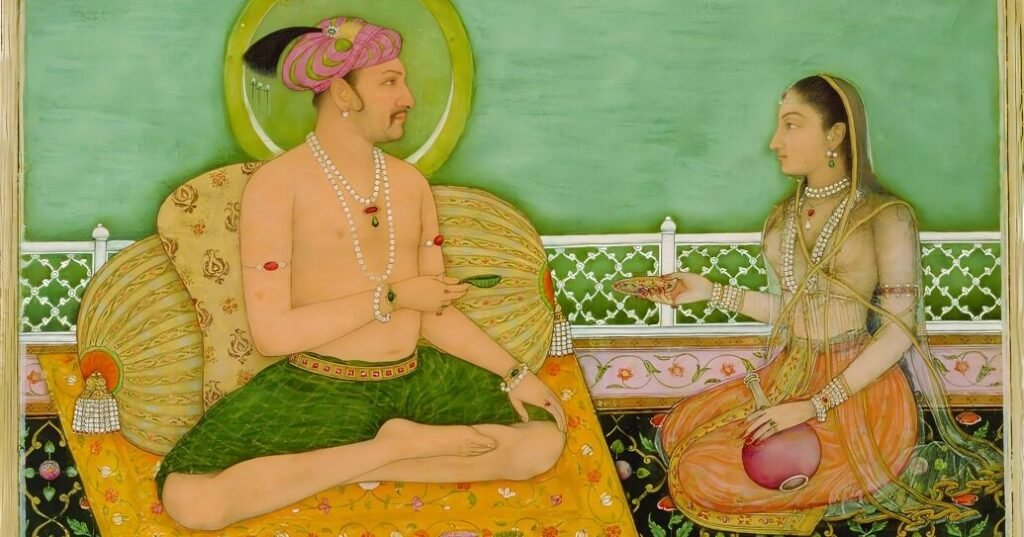

(RAHNUMA) In nearly every relationship, two opposing human needs quietly direct how love unfolds — the need for closeness and the need for independence. When these needs are balanced, love feels secure and calm. When they are not, couples often find themselves trapped in patterns of pursuit and withdrawal that leave both feeling misunderstood.

Psychologists trace these recurring patterns to what is known as attachment style, a concept first introduced by British psychiatrist John Bowlby and later expanded by psychologist Mary Ainsworth. Their research showed that the way we were cared for as children — whether our caregivers were attentive, inconsistent, or distant — leaves a lasting emotional imprint that guides how we bond in adulthood.

According to Ainsworth’s findings, only a small portion of adults have what is known as a secure attachment — the ability to love freely without fear of rejection or engulfment. The vast majority, however, fall into two insecure categories that dominate modern relationships: anxious–preoccupied and avoidant–dismissive.

Anxious–preoccupied

People with an anxious–preoccupied attachment crave closeness but constantly fear abandonment. They often overthink, seek reassurance, and become uneasy when their partner grows quiet or distant. To them, love feels safest when it is proven again and again. Psychologists note that this pattern often develops in childhoods where affection was unpredictable — sometimes warm, sometimes withdrawn — creating an enduring belief that love must be chased to be kept.

Avoidant–dismissive

Those with an avoidant–dismissive attachment, on the other hand, value independence so deeply that intimacy can feel suffocating. They appear calm and self-reliant, but beneath the surface often struggle with vulnerability. Having grown up in homes where emotional expression was discouraged or met with criticism, they learned to protect themselves by turning inward. For them, closeness feels risky, and needing others feels like weakness.

Anxious–avoidant dance

When these two types come together — the anxious who seeks closeness and the avoidant who seeks distance — they form what psychologists call the pursuer–distancer dynamic. The anxious partner reaches out for reassurance; the avoidant partner retreats to regain space. Each one’s coping strategy triggers the other’s deepest fear: one fears being abandoned, the other fears being trapped. Both want love, yet both protect themselves from it in opposite ways.

How to make it work

Despite its challenges, such relationships can succeed when both partners grow in awareness. As attachment expert Dr. Sue Johnson explains, healing begins when couples learn to understand, not judge, each other’s emotional reactions. The anxious partner can work on calming their fears before reacting, expressing needs without panic, and finding self-worth beyond constant reassurance. The avoidant partner can practice staying present even when uncomfortable, sharing emotions openly, and realizing that closeness does not threaten autonomy.

Establishing small, reliable rituals of connection — a daily check-in, consistent affection, or predictable time together — helps bridge the gap. Over time, these gestures teach the anxious partner that love is steady and show the avoidant partner that intimacy can coexist with freedom.

Psychologists call this transformation “earned secure attachment” — the ability to feel safe in love despite an insecure past. It is what happens when partners learn that vulnerability is not weakness, distance is not rejection, and love does not have to be chased or feared.

Attachment theory ultimately reminds us that most people are not broken — they are simply protecting old wounds. And the work of love, at its heart, is learning to feel safe enough to let those walls fall.